|

This is a post I should have written in March 2014 to mark the 100th anniversary of Christian Morgenstern's death. But I missed the opportunity and must be content with this belated homage.

Morgenstern (1871-1914) was a German humorist (yes, such creatures exist!) attuned to the oddities of life. Especially the idiosyncrasies of German and its use inspired many of his poems: For example, he deliberately used bad rhymes for comic effect or to gently mock the rhyming conventions of poetry1; he spun funny stories from figures of speech taken literally; he described invented creatures with names he got by fooling around with the names of existing ones; and in the introduction to a collection of his poems, he skewered the impenetrability of German academic prose. Since all of this is so tightly bound to a particular language, it's basically untranslatable. One may have better luck with poems that simply tell a story without linguistic tricks, and that's what I tried with my translation of Morgenstern's poem Der Hecht (The Pike), which can be read as poking fun at vegetarians, or religious orthodoxy, or both (see illustration on the right). The link below will lead you to the German original together with a literal translation and a rhyming Nachdichtung. Der Hecht: Original and Translations _______________ 1He shares this predilection with Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908), another master of German comic verse. |

St. Anthony preaching to the pike family |

Addendum (one day later): Since I posted this, I discovered a poem that (a) illustrates Morgenstern's penchant for taking figures of speech literally; and (b) uses a phrase that has an almost exact equivalent in English, a happy coincidence that motivated me to attempt a translation. And so I added Die beiden Esel to the first poem: Die beiden Esel (The Two Asses): Original and Translations Addendum 2 (Nov. 25, 2015): I tried my hand at a third poem, Der Lattenzaun, dear to me because an architect plays a leading role: Der Lattenzaun (The Picket Fence): Original and Translations Addendum 3 (Dec. 3, 2015): It seems I'm on a roll: Das aesthetische Wiesel (The Aesthetic Weasel): Original and Translations |

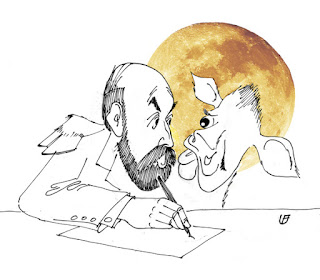

The moon calf talking to Morgenstern about the aesthetic weasel |

All Hallows' Eve

1 month ago