Word of the Month: Index

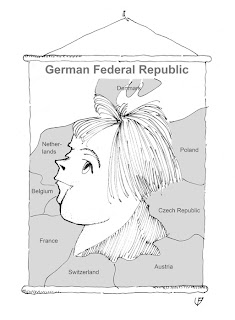

Mutti is not a compound word, and there are perfectly fine equivalents in English. That is, the WoM for January does not satisfy any of the criteria I usually apply when making a WoM selection. But I decided to make an exception, motivated by a recent, remarkably nuanced portrait of Angela Merkel, the current chancellor of Germany, in the

New Yorker (

George Packer, "The Quiet German"). Merkel is known by supporters and opponents alike as

Mutti, a diminutive of

Mutter (mother), which is used in Germany like "mom" or "mummy" is used in English-speaking countries. For my brothers and me, for instance, our mother has always been

Mutti.

On the face of it, Merkel is as unlikely a person to be called

Mutti as you could find. She has no children. She obtained her PhD the old-fashioned way—she earned it, and in a hard science to boot (as opposed to some other members of her party who had their titles taken away after charges of plagiarism turned out to be true). But she abandoned her academic career when she became interested in politics after the unification of Germany and has pursued her new career with single-minded determination ever since. Her husband is a highly-respected university professor with his own career, and the two are hardly seen together in public. In other words, Merkel is not exactly

Mutti material.

But the name has stuck. Merkel won her third election in 2013 (the third chancellor of the Federal Republic to accomplish this feat) with a campaign that was remarkable for its absence of big themes or grandiose visions. Her point was, "Stick with me and you're safe." Clearly, a large number of Germans bought it* and do not hesitate to call her

Mutti, in a half-mocking and half-admiring way (that she looks the part, in a particularly dowdy fashion, may also play a role, particularly for those who use the moniker more derisively).

And there are many of those, if the comments I read on political blogs are in any way representative. In fact, there seems to exist an almost visceral hatred of her in parts of the left. Some of it may stem from old-fashioned snobbery—anything that's popular cannot be good by definition. But the hatred seems to sit deeper, and I find a clue why this may be so in a quote by a Social Democrat cited in the

New Yorker article, "Merkel took politics out of politics." And that is anathema for those to whom ideology is the only thing that matters in politics; for those who are against a measure when it's ideologically incorrect, even if it works in practice, and conversely, are

for a measure when it is ideologically correct, even if it does

not work in practice. So, the common complaint against Merkel is that she has no vision and is just "muddling through" (

durchwurschteln in German).**

I'm too far away to have a definite opinion on this (and would welcome comments from people closer to the action). But there are two traits of her I admire from my distant perch. It's first of all her ability to remain

unaufgeregt ("unperturbed"), even when faced with attacks and insults of the most vile kind, as they happen routinely in countries unhappy with her fiscal policies and having a press that appears to be in a state of permanent hysteria. My favorite cartoon of 2014 (which I cannot show here because of copyright issues) was sent to me by my friend Volker Sayn. It shows a row of spectators looking after a group of politicians that just passed by, with a dowdy-looking woman in a pant suit in the center. Says one spectator to his neighbor, "That was Merkel? I did not recognize her without the Hitler mustache."

And she does not make a mistake twice. In her first election, she had run on a platform calling for continuing the economic reforms initiated by her (social-democratic) predecessor and had made an economics professor a member of her advisory team. He, in turn, used the occasion to introduce one of his pet projects, a flat tax rate, into the debate—and this in a country that firmly believes, across the political spectrum, in progressive taxation and despite the fact that absolutely nobody else regarded this an issue. The electorate was confused, and Merkel almost lost the election. She never again ran on a platform calling for significant reforms in any shape—her supposed lack of vision may be based on this experience.

A second example: When the Euro crisis started for good with Greece going practically bankrupt in 2010, Merkel called for leaders of the Euro Zone to get together and work out a general solution "in solidarity," only to learn that nobody wanted to follow her lead because it would inevitably imply the loss of some sovereignty for the countries involved. Merkel never suggested this again and has been trying to muddle through the crisis ever since. [If there's one principle she keeps in mind, it's not to "throw good money after bad" and to protect the German taxpayer from having to bail out countries that got into the mess they are in through their own fault (and many Germans love her for it).] I think she knows that when other countries call for Germany to assume more of a leadership role, it's a euphemism for asking the Germans to write blank checks for everyone asking for them—when German politicians suggest something else, like the need for some structural reforms, they are invariably chastized for "trying to tell other people what to do." [What's positively infuriating to some Germans is that at the same time, everybody feels perfectly fine lecturing the Germans about what

they ought to do.]

If there is one issue where I believe leadership on the European stage is urgently needed (at no immediate cost for anybody), it's to impress upon the generations that have not grown up in the immediate aftermath of WWII that the European Union is an achievement of singular historical significance for a continent that has seen the type of bloodshed Europe has experienced for thousands of years. But alas, Merkel is not suited for this role—as the article mentions, she is an awkward public speaker, which is a polite way of saying charisma is not her forte.

________________

*Merkel won 86% of the electoral districts. If Germany had a system like the UK, Merkel's party would have controlled 86% of the seats in parliament. But since the final distribution of seats reflects the percentage of votes obtained by each party overall, Merkel had to form a coalition government in order to gain a parliamentary majority.

**Lindblom's

The Science Of 'Muddling Through' (1959), a manifesto of Anglo-Saxon pragmatism, has never made an impression on "principled" Germans.